Copycats have a bad reputation.

These days people prize originality. We laud individuality. We’re secretly disappointed if ours kids color inside the lines.

But before the 20th century, originality was not expected of students, writers and artists.

Copy work is craft

People learned by imitating masters. Virgil copied Homer. Michaelangelo copied Donatello. Manet copied Raimondi.

And now I’m copying Irving Penn.

It all started last spring with a photography class I took at NYC’s Fashion Institute of Technology.

My Copycat Photo Assignment

The instructor asked students to choose a famous photographer and shoot a series of photos in the manner of the master. I wanted to learn food photography I so chose Penn.

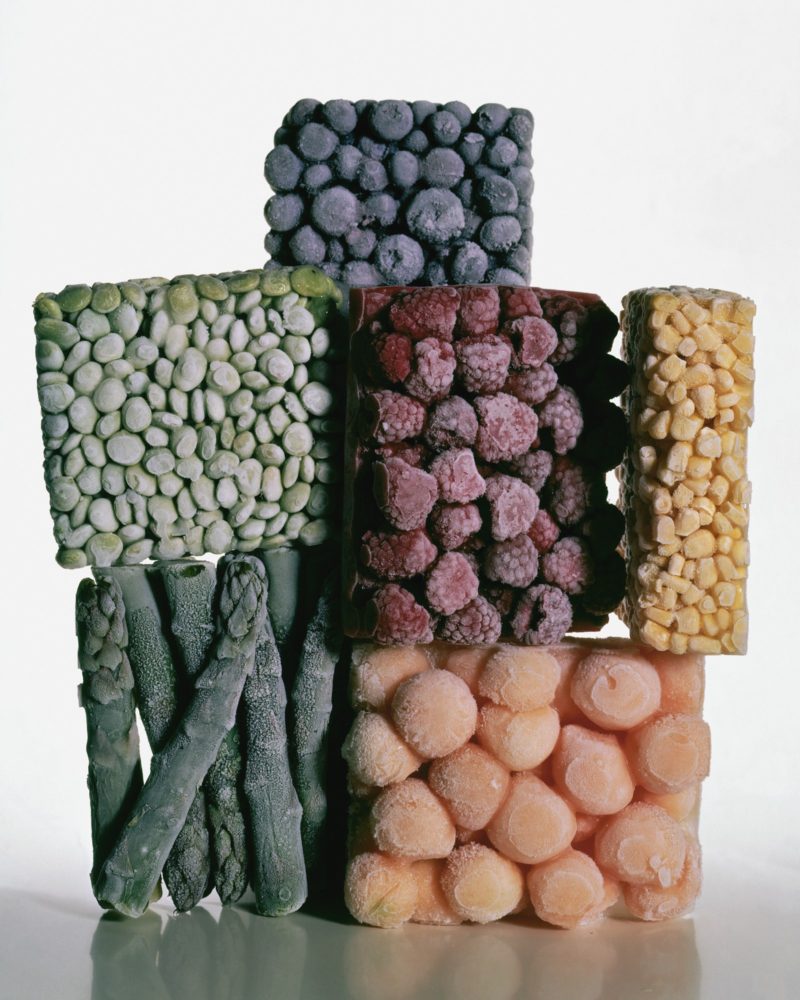

As a kid in the 70s, I’d stumbled on his food still lifes in Vogue. Nestled between glossy spreads of body-painted models and Kent cigarette ads, the photos were oddities–but clearly Art. Penn’s colorblock frozen food had more in common with Ellsworth Kelly than the Jolly Green Giant.

Irving Penn’s Modernist Still Life Photos

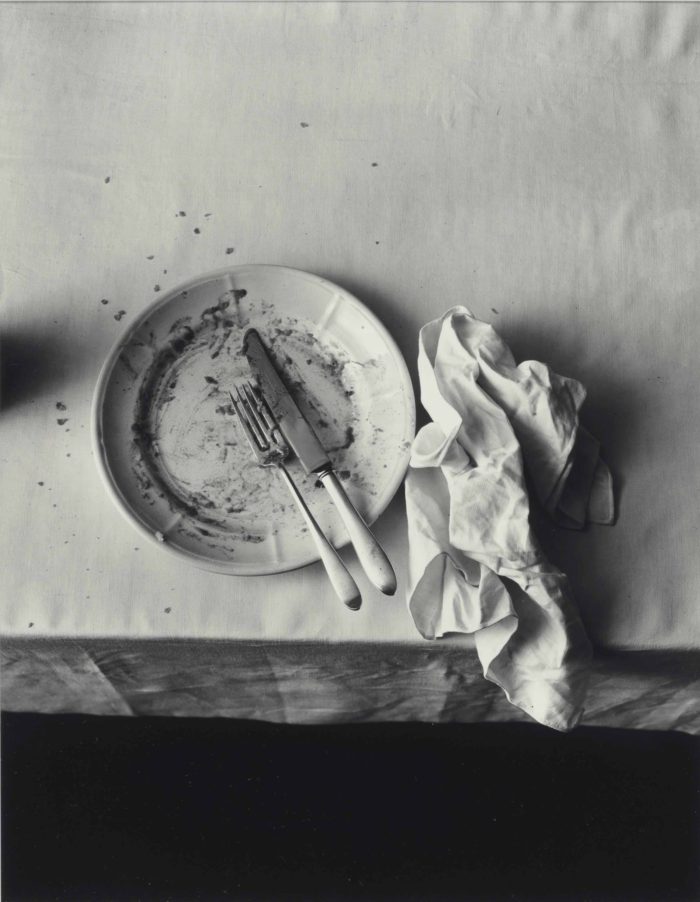

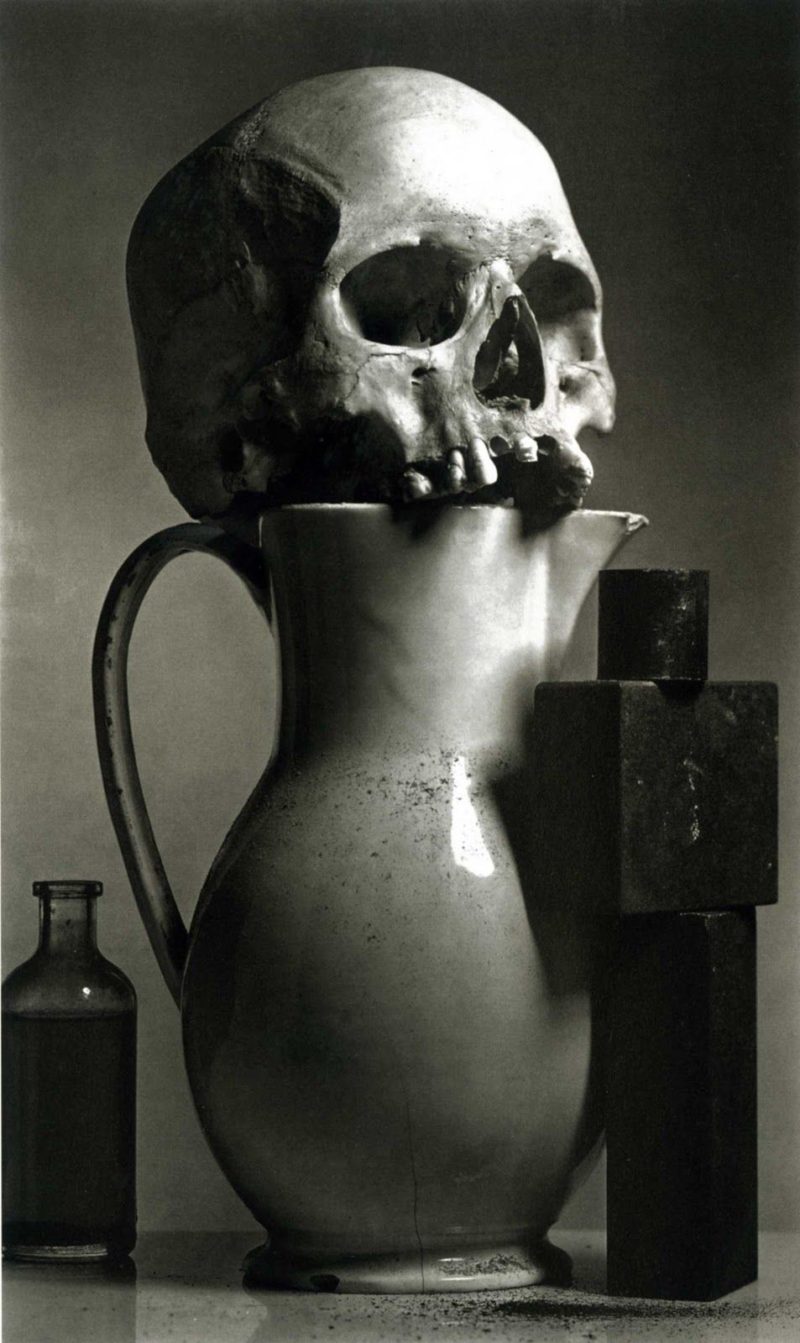

Penn’s work spans fashion, formal portraiture, advertising, ethnography and still life photography. His photos use the composition, light and subject matter of older art works such as Dutch still life painting, modernist hard-edge painting and 18th century portraiture.

Looking at them is a layered experience. There’s a whiff of something you recognize as ancient but the works are unmistakably modern. And they remain contemporary 50 years later.

I chose six of Irving Penn’s still life images, copied them as closely as possible and didn’t come close.

Penn makes it look so easy and effortless. The harmonious composition. The perfect natural lighting. The perfect studio lighting. The masterful use of color. And his easy way of communicating with his subject, whether it’s a Peruvian shepherd or a stack of quick-thawing frozen corn.

Here are the master’s work and my copies…